The following is Part 2 of a two-part article by R. Dennis Green. If you missed Part 1, be sure to check out our last issue of 2019!

Part 2: Looking Back 40+ Years…

Part 2: Looking Back 40+ Years…

In an Era of Constant Change, Some things Don’t

I love the proposal management profession, as previously stated. And there isn’t a single workday that my heart doesn’t race with competitive excitement and the thirst to help a good client win.

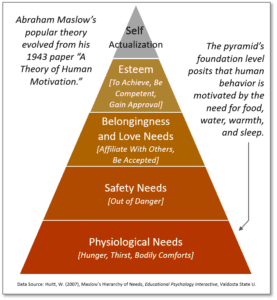

It’s just one facet of my romance for the business that has never changed. Many others I’ve met in industry find proposal work disagreeable. There’s literally nothing they’d rather not do. But it’s always been different for me. It seems to satisfy some innate need. Put in the context of Maslow’s Hierarchy of Needs, shown in Figure 2, this work puts me at the top of Maslow’s theoretical pyramid – fulfilling the need for “Belongness and Love” (friends), “Esteem” (feeling of accomplishment), and “Self-Actualization” (achieving one’s full potential) to the fullest degrees.

If the reference to Maslow is unfamiliar, Abraham Maslow (1908-1970) was a widely-renowned psychologist and professor who attempted to synthesize the large body of research then related to human motivation. He introduced his concept in a 1943 paper, “A Theory of Human Motivation,” and evolved it more fully in his 1954 book Motivation and Personality.

If the reference to Maslow is unfamiliar, Abraham Maslow (1908-1970) was a widely-renowned psychologist and professor who attempted to synthesize the large body of research then related to human motivation. He introduced his concept in a 1943 paper, “A Theory of Human Motivation,” and evolved it more fully in his 1954 book Motivation and Personality.

He’s also source of the popularly phrased business metaphor: If all you have is a hammer, everything looks like a nail.[1]

I’ve always been intrigued by Maslow’s theory and, by extension, I wanted to articulate a “hierarchy of needs” for our profession. And, once that new hierarchy was put into words, the question to consider—looking back at my 40-year experience—was whether that hierarchy of needs had been changing? Had the whirlwind of technological change and innovation experienced in my lifetime altered capture and proposal management’s foundational needs?

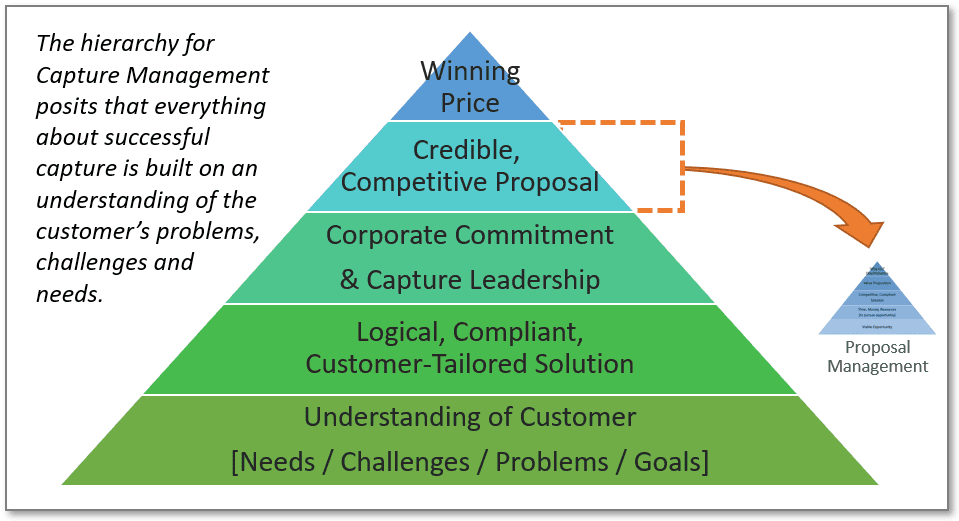

To date, no one has tried to view our profession through Maslow’s prism, but it doesn’t seem difficult to do. APMP’s Body of Knowledge (BOK) provides an ample resource of candidate “needs” and hints at their probable ranking. Viewed through the BOK and my own experience, I created a Maslow-inspired mockup of what that hierarchy of needs might look like. It’s a two-part hierarchy, shown as Figures 3 and 4.

Figure 3. Hierarchy of Needs — For Capture Management, Inclusive of Proposal Management

The hierarchy of needs for capture management is built, in its entirety, on an understanding of the customer. That singular need is the building block on which all other capture management needs are placed. If you don’t understand your customer’s problems, challenges, and objectives, you will be bidding blind. Once you have an understanding of the customer, you can create a tailored solution. As a bidder, that customer-centered solution is your next-level need, your next building block in the hierarchy. Corporate commitment is a need because it is critical to ensuring that resources are in place to deliver the promised solution. The ‘Why Us’ argument for that solution is put forward in your proposal and in a winning price.

As a whole, the needs in this hierarchy are complementary and codependent. If unfulfilled, the absence of any one need will jeopardize the likelihood of a win.

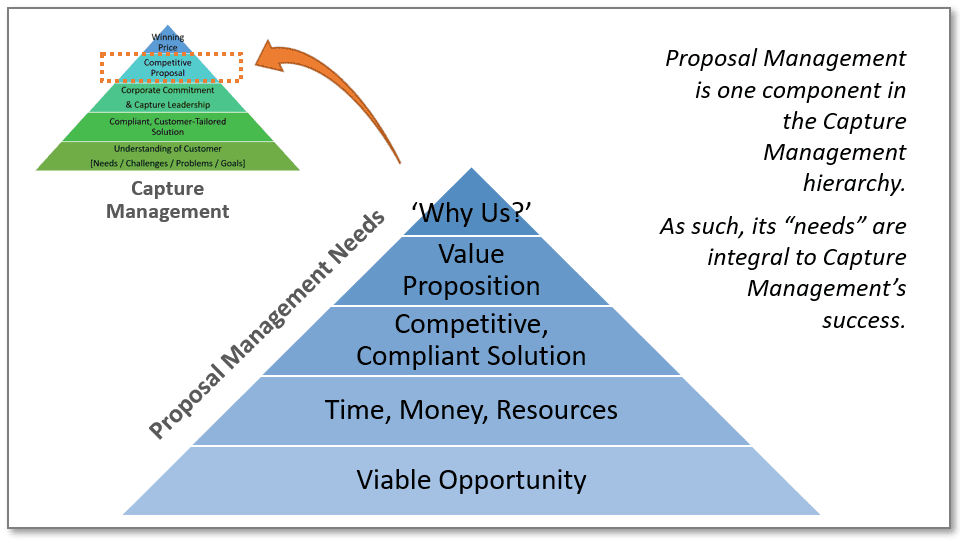

The Proposal Management component (step four of the Capture Management hierarchy) enjoys its own subordinate hierarchy of needs, as shown in Figure 4. In a secondary but similarly-structured pyramid, the needs for proposal management include a “Viable Opportunity,” “Time, Money, and Resources,” a

“Competitive, Compliant Solution,” a compelling “Value Proposition,” and clearly-articulated “Why Us?” discriminators with the power to hook the evaluators attention and persuade them your solution is the superior choice.

Figure 4. Hierarchy of Needs — For Proposal Management

As shown in this two-part hierarchy, at a theoretical level, the underlying needs for winning have remained impervious to change. New technologies and innovations may be inherent to one or more levels, but those technologies don’t alter the actual needs.

Aristotle Agrees. This conclusion about the resilience of basic needs mirrors an analysis performed about the roots of persuasive argument for APMP’s Professional Journal, Proposal Management, in the Fall of 1999. In it, we asked Roger Dean, managing partner of Engineering Proposals, to help us evaluate this very question. In his article, “The More Things Change, The More They Stay the Same,” Dean succinctly summarized the roots of persuasive argument, reaching back to Aristotle’s Rhetoric, written in about 350 BC.

Dean observed that Aristotle’s treatise recognized “two fundamentally different modes of persuasion: one that comes from the ability to apply some sort of force (that might be called the ‘[gangster] method’) and one that relies on language alone (the original definition of ‘rhetoric’).” Rhetorical persuasion, Dean argued, is all we have when it comes to proposals, as much as we might wish otherwise. The elements Aristotle identified as essential to rhetorical persuasion were: the character of the speaker, the mindset of the audience, and the logic of the argument. “In proposals—written and oral,” Dean wrote, “you must be perceived as credible from the start, you must appeal to what is important to your audience, and you must present a logically consistent argument, including adequate supporting evidence.” Similar precepts are echoed in the preceding hierarchy of needs.[2]

My conclusion today is the same as Dean’s was, 20 years ago. In spite of the modern world’s innovations and a bombardment of new technologies, the keys to persuasive argument haven’t changed. Likewise, hierarchies of need for capture and proposal management endure.

[1] “Trends & Views: The More Things Change, The More They Stay the Same,” by Roger Dean, Proposal Management Journal, APMP, Fall 1999, Pgs 9-11.

[2] In Maslow’s original phrasing, it was: “I suppose it is tempting, if the only tool you have is a hammer, to treat everything as if it were a nail.” From: The Psychology of Science: A Reconnaissance (1966), by Abraham Maslow, Ch. 2, pgs. 15-16.

Leave A Comment