No one wants to lose, and no one wants to talk about losing. It is like talking about death. But failure can be an effective teacher.

Most proposals are losing proposals—a statistical fact that is often ignored. But this does not mean that the participants are losers. Consider the career of Mike Krzyzewski (Coach K), a basketball legend who inspires his players to greatness. Under his direction, the Duke University basketball program has become one of the most successful in the history of the sport. Coach K has been selected as National Coach of the Year 12 times and has been inducted into the Basketball Hall of Fame. By any objective standards, he is a winner. Yet 31 of his 34 seasons at Duke have ended with a losing game. After all, at the end of any season, only one team wins. In proposals, as in basketball, there is just one winner. Even in the case of large contract competitions, which sometimes do result in more than one winner, the subsequent delivery or task order competitions narrow the field down to one.

Why Talk About Losing?

The reasons to study losing are numerous and compelling. The first is that uncomfortable statistic: most proposals lose. Therefore, all proposal professionals experience a loss at some point. In fact, corporations already accept the fact that losing is inevitable, and that is why the values of opportunities in the pipeline are weighted according to win probability. No one would believe a forecast if it assumed a 100-percent win probability for all opportunities in the pipeline. Of course, at the level of the individual deal and the individual proposal team, everyone involved has to believe that winning that particular deal is at least possible, if not likely.

If losing is inevitable, it is imperative that proposal professionals find a way to deal with it and ultimately benefit from it. Instead, many proposal professionals—and managers, executives, subject-matter experts, and production staff—bypass the opportunity to learn from a loss. Individuals and the organizations they work for try to forget about it, deny it, rationalize it, blame it on something, or engage in unyielding self-criticism. Moreover, losing is important because, for both psychological and cognitive reasons, failure is a better teacher than success. Most people know this instinctively from their own experience, and it is substantiated in empirical studies (Edmondson, The Hard Work, 2005; Ulmer 2006). Errors “provide a ‘clear signal’ that facilitates recognition and interpretation of otherwise ambiguous outcomes,” and failure “provides a ‘learning readiness’ . . . difficult to provide without a felt need for corrective action” (Sitkin, 1996). In a study of the neurological foundation of learning, Jonah Lehrer observes, “Unless you experience the unpleasant symptoms of being wrong, your brain will never revise its models. Before your neurons can succeed, they must repeatedly fail. There are no shortcuts for this painstaking process.” (Lehrer 2009) In the final analysis, proposal professionals are lucky because the events from which people learn the most—losses—are ones that they will inevitably experience. Finally, losing merits attention because learning from failure is difficult and must be approached in a careful and sometimes counterintuitive way to be successful.

This article sets forth four steps that facilitate learning and growing after a loss. It examines the literature that documents the approach to failure in other contexts (health care, aviation safety, entertainment, foreign aid, and military training) and explores the reasons why organizations find these steps so difficult to implement. For each such reason, the article presents remedies and techniques that proposal teams can use. Finally, it addresses the need for a code of conduct after a loss.

The Four-Step Process

Proposal and capture teams need to go through four steps to benefit from a loss. These steps are based on common sense, observation of how proposal teams behave, and insights gleaned from literature from other disciplines. They are derived from, and align with, the following process developed at the Center for Creative Leadership: “exploring, reflecting, and projecting” (Ernst 2006).

The four steps are:

1. Find out what happened

2. Determine causality (i.e., determine which events, decisions, or thought processes were actually responsible for the loss)

3. Take action, if appropriate, based on lessons learned

4. Let go and move on.

Each step must be performed sequentially to be effective. When teams rush the process, they are likely to err in either their analysis or their corrective measures. What actually happened must be determined before the question of causality is tackled, because of the many unfortunate events that can occur during a proposal only a subset constitute the actual cause of the loss. Taking action needs to be postponed until all the fact-finding and analysis are done; otherwise, teams are likely to take the wrong action. Trying to move on without completing the first three steps leaves participants with a nagging sense that there are loose ends, and it saps energy from future endeavors.

Each step, though fairly simple in concept, is often performed in the most superficial way in both large and small companies—if at all.

Step One: Find Out What Happened

This step sounds straightforward. In fact, it is an emotionally challenging and intellectually demanding task. The team must dispassionately review the entire history of the procurement. They must ask detailed questions and dig into the specifics of the deal without assigning blame or trying to settle old scores.

It means carefully examining the relevant documents, including capture plans and briefings, the presentations prepared for gate reviews, teaming agreements, solution charts, color-team review inputs, and the proposal itself. It takes time and attention to detail, and it depends heavily on documentation. Without an audit trail, those conducting the assessment have to rely on interviews and the vagaries of human memory, and the process will take much longer.

Proposal professionals depend on best practices and repeatable processes, but each opportunity is unique, and each post-loss fact-finding exercise is also unique. Thus, although it is tempting to use a checklist to complete the post-loss analysis, an overly rigid analysis will prevent the team from uncovering what really happened. A variety of approaches are worth considering, and which is best will depend on the specific opportunity. One approach is to assess events according to function: pricing, customer relationships, solution, etc. Another is to approach the opportunity from a chronological perspective. A third is to look at critical decisions that were made along the way. This is a time to ask tough questions and challenge accepted wisdom about corporate policies and established routines. The best practice in the world might not have been the right one for this specific opportunity.

Step Two: Determine Causality

The second step is to determine the underlying reason or reasons for the loss. This means going through the long list of events assembled in Step One and determining which actually caused the loss. Determining causality is not the same as conducting root-cause analysis. The distinction is subtle but important. Root-cause analysis gets to the core of why a specific event turned out differently than desired. But that particular event, however unfortunate, might be unrelated to the loss. Confusing correlation and causation is a common error made by proposal teams after both wins and losses. Interestingly, it is also made when studying successes in general. Jerker Denrell highlights the pitfalls of perceiving causation where it does not exist through an absurd example involving successful executives. All successful executives have one thing in common: They all brush their teeth.

Of course, so do unsuccessful executives. So, tooth-brushing does not necessarily result in success (Denrell 2004). In the proposal environment, it is easy to assume that the team won because of a highly technical and well-documented solution. Yet the team might have actually overcomplicated the problem and won in spite of the solution and not because of it. It is even easier to jump to these types of conclusions after a loss. How can teams determine causality? First, do the work required to get through Step One and do not stop until it is done thoroughly. Second, get a formal debrief from the customer and put that debrief in context. Most teams that do not do the analytical homework described in Step One rely disproportionately on the customer debrief. Information provided at a debrief might explain or lead to an explanation of the underlying reason for the loss, but it might not. Debriefs are inherently contentious events. Both sides enter the discussion with apprehension. Some bidders are tempted to defend their proposal; some argue with the government contract staff. Very few people, including mature professionals, take criticism well. Even if everyone involved remains calm, it is not always easy to get to the underlying reasons. Sometimes the evaluation of the proposal appears to be based on generalities rather than specifics. And government customers are subject to the same psychological biases that affect proposal teams.

Sometimes different government opinions have to be reconciled, and the final decision might not reflect the range of views on a proposal. At the same time, customer debriefs often reveal legitimate shortcomings of the proposal or the solution. Nonetheless, even if all debriefing material can be taken at face value, it has to be carefully weighed.

Ultimately, the information from the debrief has to be weighed fairly and rigorously against all other data points collected during the post-loss analysis. It is a set of data points. It can neither be entirely ignored nor taken entirely at face value. Determinations of causality will always be partially subjective. Yet thorough documentation and careful analysis by individuals with both experience and good judgment can reduce the degree of subjectivity.

Once the team has determined the cause of the loss, it is equally important to assess other perceived failures, errors, miscalculations, or problems with the process. Just because those events did not lead to a loss this time does not mean that they do not merit attention. They might cause a loss the next time. In assessing these other events, it is important to get different perspectives. Was the event a function of unique circumstances, or did it reveal a systemic weakness? The author and journalist Alan Beattie recalled a biologist telling him that all biologists could be categorized as either “lumpers” or “splitters” (A. Beattie 2009). Lumpers tend to group things together and develop rules to explain that group; splitters see each event as unique and in a specific context. In a post-loss analysis, both perspectives are needed. Some events are flukes. Others are part of a pattern.

Conversely, there are instances when a loss is not the result of a failure or mistake. This is a critical determination because, if this circumstance is not correctly identified, teams might try to fix what is not really broken, and they might discard valuable processes, techniques, and potentially reusable proposal content. Many proposal professionals instinctively assume that there is always a way to win in any situation. But this is not always true. No team has perfect knowledge and uncontrollable events do occur.

Step Three: Take Action

The work entailed in Steps One and Two is demanding onmany levels. Yet it is not worth doing unless the organization is prepared to follow through on the remaining steps. Investing the resources required to acquire knowledge but then failing to follow up on it has repercussions for organizational efficiency and team morale. Analysis must be followed by action. The most efficient way to approach this step is to examine all the events discovered in the previous two steps and categorize them. (This is when to get the “lumpers” involved.) Most proposal errors, failures, and weaknesses fall into one of the following categories:

• Weak leadership

• Errors in judgment

• Inadequate procedures

• Procedures not followed

• Having the wrong person fill a role

• Not assigning enough people to a particular function

• Inadequate technology (for collaboration, production, etc.)

• An insufficient proposal budget

• Poor planning and scheduling

• Insufficient or inaccurate customer knowledge

• Inadequate information about the competition.

Once this list is compiled, it is important to get the perspective of the “splitters.” This is because an action-item list, the output of Step Three, should be driven by systemic weaknesses or flaws, not one-time events that are unlikely to occur again. The splitters can identify the unique events. Some examples include:

• The competitor made two acquisitions that added critical capability late in the proposal cycle.

• Important decision-makers in the customer organization were removed from the process due to unforeseeable

events after the proposal was submitted.

• A natural disaster, such as a blizzard or a flood, prevented key players in the proposal process from attending orals rehearsals.

No organization can develop processes that anticipate all contingencies, and no organization can afford to go down that road. However, many proposal events reveal systemic flaws, and these form the basis for the action-item list. Although priority is necessarily attached to the events that actually resulted in the loss, other weaknesses or problems can be of equal importance. Resources are finite, and not every flaw can be addressed.

Items on the list can include training, hiring, firing, acquiring new technology, reassigning personnel, and developing new approaches to customer intelligence gathering, to name just a few. A professional must take ownership of the action-item list and, for each action, identify the following:

• What needs to be accomplished

• What the interim steps are

• What the relevant milestones and deadlines are

• How the team will know when the problem has been fixed

• Who will be responsible.

Whoever owns the list needs to schedule regular meetings until all the action items are addressed. Because taking action always demands resources above and beyond what was planned for, senior leadership buy-in and support are critical.

Step Four: Let Go and Move On

Conscientious professionals always want to learn more, but the amount of useful knowledge that can be gleaned from revisiting the same ground over again diminishes after a certain point. Strong leaders know when to stop. It will be easier to move on if the analytical work of figuring out what happened and the follow-up work of changing whatever needs improvement are completed. Loose ends make it difficult to take on a new challenge. This is a good time to make sure that the housekeeping is done. Create any additional proposal copies required for the archives, consolidate and label files, close down websites or collaborative workspaces, and so forth. Clear out the proposal room, just as the crew starts striking the set the same night of a play’s last performance. Small symbolic actions reinforce closure and make it easier to turn to a new page. Finally, senior managers should recognize the hard work and sacrifices of the team. Losing is rarely the result of intentional error or negligence, and recognition is all the more important when there are no bonus pools or other tangible rewards.

Obstacles and Remedies

Each of the four steps described above is based on logic and common sense: determine what went wrong, and fix it. Why do so few organizations take these steps? It is because there are serious obstacles fighting against them. In effect, proposal and capture teams have to climb steep mountains to accomplish each one.

To understand why these mountains are so high and what has to be done to climb them (as opposed to circumnavigating them), it is useful to examine other arenas in which failure occurs and to see how people and organizations address them. These include the broader business world. Few other situations in business—or

in life—are directly comparable to the experience of proposal teams, which operate in winner-take-all situations. Yet, concepts and ideas from these other fields and disciplines have much to offer if they are applied selectively. The fact that these concepts have been studied and tested on larger populations and over a longer period than would be possible in the proposal environment makes them all the more compelling and worthy of our interest.

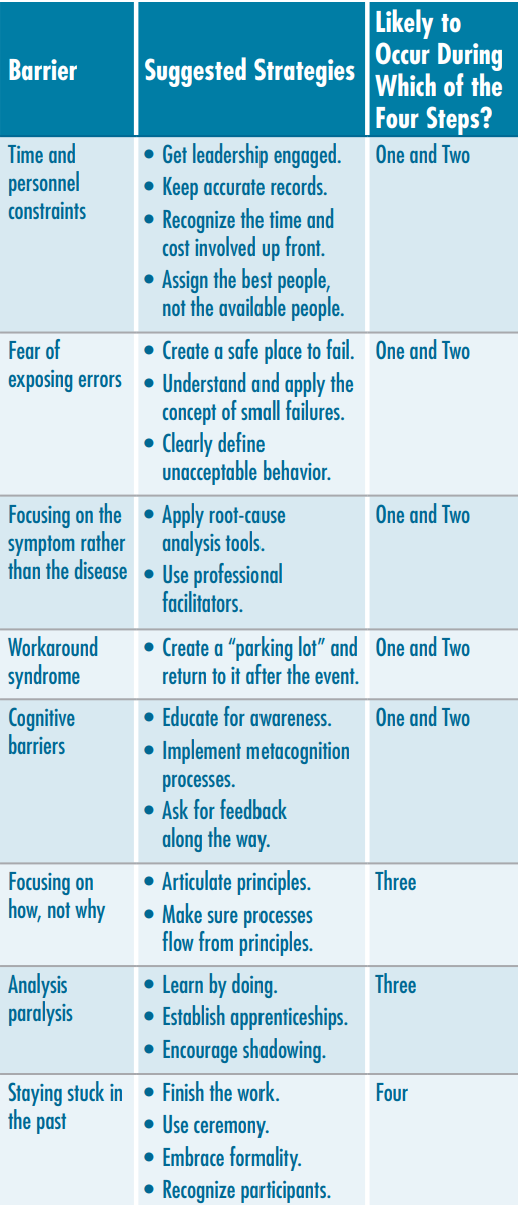

The experience of professionals in other fields suggests that there are at least eight different reasons why companies do not learn from losing proposals:

1. Time and personnel constraints

2. Fear of exposing errors

3. Focusing on the symptom rather than the disease

4. “Workaround syndrome”

5. Cognitive and psychological biases

6. Focusing on how, rather than why

7. “Analysis paralysis”

8. Staying stuck in the past.

Each obstacle can be overcome once it is acknowledged and understood. Each is explained in brief and followed by a suggested remedy below.

Time and Personnel Constraints

One of the many reasons why so-called lessons-learned exercises turn out to be neither lessons nor learned is logistical and practical: time constraints. Because each opportunity is different, understanding what happened demands attention to detail, and, if time is in short supply, that level of attention will be insufficient. According to Amy Edmondson of Harvard Business School, “conducting an analysis of a failure requires a spirit of

inquiry and openness, patience…”. However, most managers are rewarded for decisiveness and efficiency rather than for deep reflection and painstaking analysis (Edmondson, The Hard Work, 2005). The fact that failure is an

unpleasant topic only increases the likelihood that participants will rush through the analysis. Lack of knowledge and experience are also very real challenges. Because each opportunity has to be seen in context, the details, some of which may be technical, matter. If a corporation assigns whatever senior staff member might be available to conduct the analysis, that individual might not have the requisite knowledge and experience. Root-cause analysis demands objective, rigorous thinking by people who are not afraid to question traditional wisdom. Furthermore, a careful

analysis of everything that happened requires contributions from everyone who played a significant role, including the business development team, the capture team, finance, legal, engineering, and so forth. Time and personnel constraints are intensified by poor documentation. Often the key decision points in a capture and proposal effort are not recorded accurately in the records and have to be recreated based solely on human memory.

How can these constraints be overcome? There is no panacea for a company unwilling to spend the time or assign the

appropriate people to learn from mistakes. Time and resource constraints have to be addressed by senior management. Professionals will spend time on activities that are valued implicitly in the corporate culture and explicitly through tangible and intangible rewards. Good records are not difficult to create, and this is

one area in which proposal and capture teams can take corrective action that will help in the event of either a loss or a win.

Fear of Exposing Errors

A second barrier to exposing the entire history of the opportunity, which is the first step on which all the subsequent ones depend, is the fact that people, reluctant to reveal their mistakes, devise elaborate ways to disguise them. Organizations face a difficult balancing act with respect to accountability. Without clear lines of responsibility, there is little incentive to avoid errors, and few organizations are willing to espouse a policy of tolerating error. However, if accountability and personal responsibility become the basis for assigning blame, a culture of fear and finger-pointing develops and precludes the identification of serious problems that need attention (Edmondson 1996). In many organizations, the lessons-learned process after losing a bid becomes an opportunity to assign blame. The way to overcome a fear of exposing errors is first to recognize that corporations already tolerate some degree of error. Otherwise, everyone who worked on a losing bid would be fired, and all opportunities in the pipeline would carry a 100-percent win probability. But there is a difference between accepting errors implicitly and creating a culture where they come to light in a productive way. There needs to be enough acceptance of exposing errors that the facts will come to light without creating a climate where persistent errors are accepted as a matter of course. Three concepts from other fields can be adapted to address the fear of exposing errors: (1) the idea of just culture, a term used in the medical community to address errors; (2) a methodology for setting boundaries; and (3) the concept of small failures.

Just Culture

The just culture concept originated in aviation safety and has since been adopted by the medical community. It is a philosophy that “seeks to balance system and individual accountability for patient safety and to base disciplinary action on behavioral choices. . . . A nurse misreads the label on a medicine vial and gives the patient the wrong drug. She is not incompetent, merely human. A just culture recognizes this and attempts to reorganize the system so human errors are trapped before they reach the patient” (Decker 2007).

Just culture classifies different types of errors and addresses them with appropriate responses. In medicine, these classifications are human error, at-risk behavior, and reckless behavior. In the proposal environment, an example of human error is the kind of mistake an author or desktop publisher makes after working too many consecutive hours without enough sleep. Introducing new concepts into a proposal without vetting them through the leadership team is an example of at-risk behavior. And leaving a copy of the proposal in a place where it could be seen by competitors clearly constitutes reckless behavior. By classifying proposal errors, organizations can develop more effective responses instead of assigning blame and applying a standard remedy regardless of the classification or the context.

Setting Boundaries

Setting boundaries follows logically after errors have been classified. These boundaries have the paradoxical effect of reducing fear rather than increasing it. If people do not know where the boundaries are, they will be even more reluctant to reveal the facts about what has happened because they are unsure what is inside and outside the boundary of acceptable conduct. When unacceptable behavior is clearly defined, events that do not fall into that unacceptable category are more likely to come to light during a lessons-learned process. If it is not defined, errors that need to be corrected might remain forever hidden. For this reason, it helps to publicize what constitutes punishable misconduct (Edmondson 2004). In the proposal environment, an obvious example of unacceptable behavior is getting lost on the way to deliver the proposal and failing to call for help. Another is failing to keep a backup copy of the proposal files. Maintaining a just culture and defining limits provide proposal teams with what they really need in order to learn from mistakes: a safe place to fail. Implicitly we accept that there will be mistakes

on a proposal. Otherwise, there would be no need for quality control and color reviews. That acceptance needs to be made explicit if errors are to be uncovered in time to be fixed, whether during the proposal or before the next bid.

Small Failures

Creating a safe place to fail is consistent with the notion that it is more effective to learn from what Sim B. Sitkin, an organizational behavior expert from Duke, has described as “small losses.” Sitkin advocates finding small contained failures or errors and using these as the basis for improving performance. Rather than waiting for a postmortem after the award, teams should constantly look for failure and perform lessons-learned exercises on a smaller scale whenever there are errors that meet one or more of the following conditions:

• They resulted from planned actions

• Their outcomes were uncertain

• Their outcomes were modest in scale

• They resulted from short-duration activities

• They were relevant to the core business and core competency

In the proposal environment, the concept of small failures is inherent in the color-review process. If proposals were created perfectly the first time around, there would be no need for these reviews. Too often, however, the color-review process is elevated to the status of a large failure after which people assign blame rather than learn lessons. One remedy is to set clear expectations before the review starts and emphasize that the goal of the review is not for the team to come away with a perfect score but rather to identify areas for improvement.

Focusing on the Symptom Rather Than the Disease

Organizations engaged in a postmortem tend to focus on the symptom rather than the disease. If the proposal did not contain information relevant to the customer, it is easy to determine that the cause was an inexperienced proposal manager or proposal writer. In fact, the underlying reason might be that the business development team was never able to get good customer information to pass along to the proposal team. This phenomenon of focusing on the symptom rather than the disease is compellingly examined by Amy Edmondson, who writes, “When only the superficial symptoms of complex problems are addressed, the underlying problem typically remains unsolved, and even can be exacerbated if the solution feeds into a vicious cycle (such as providing food as direct aid, which relieves the starvation but perpetuates the problem of population growth in inhospitable climates)” (Edmondson 1996).

Specific tools for performing root-cause analysis can be applied to get past the symptom and focus on the disease. Here again, the scholarly literature is useful for learning from a proposal loss. The root-cause analysis concept originated in manufacturing and is often referred to as “the five whys” because Toyota discovered that, on average, it took an average of five “whys” to get to the root cause (Casey 2008). Masaaki Imai proposed this approach

at Toyota in the 1970s to improve the diagnosis of production problems. It entails continuing to ask why each event occurred until the root cause is identified. The consulting firm Critical Thinking defines root-cause analysis as “uncovering how the current problem came into being. . . . You know you are done gathering information when you see the complete picture of how this particular problem came into being and are ready to consider what to do about it”. For example, perhaps the post-loss analysis reveals that the proposed management team was not experienced enough to be credible to the customer. This is the time to ask the first “why.” Suppose the answer is, “The top two candidates for the management positions were not available and could not be bid.” Then the team would ask the second “why.” If the answer is something like, “They could not get approval to get time off from their ongoing

contracts,” it would be time to ask yet another “why.” Suppose the answer to that is, “Their managers did not see the value in their participation in the proposed project when compared with keeping them billable on current work.” Now it would be time for one more “why.” The answer to that might very well be, “No one from senior management called the supervisors to explain that this was a ‘must-win’ or offered any assistance in filling the gap that would be created by the candidates’ absence.” This is a real-world example of a root cause, and it is a problem that can be addressed or avoided the next time. Ironically, many proposals include a detailed description of root-cause analysis, as it is used in the management of information technology resources, but the same teams that developed those very proposals do not use the technique to analyze their own experiences. The U.S. Army has a detailed manual that prescribes the steps for an after-action review as do other US government agencies. Because of biases that the members of the proposal teams themselves might not recognize, it helps to have an experienced facilitator manage the root-cause process. Moreover, conversations about personalities, work habits, competencies, skills, knowledge, and experience can enter into the root-cause analysis. These are sensitive topics, and the entire exercise can easily degenerate into assigning blame unless there are clearly stated and enforced rules of the road and one or more neutral observers.

The Workaround Syndrome

Proposal professionals become adept at addressing the immediate problems, even to the point of not recognizing whether those problems are related to an underlying root cause. When I worked in an office where the humidity was so high that it warped the paper, I regularly bought paper just before the proposal was printed and kept it at home. After a while, it was just part of the routine, and I stopped seeing it as a problem. This phenomenon is also seen in the hospital environment, where nurses pride themselves on acting independently to find whatever the patient needs

rather than taking action to identify, much less fix, underlying organizational problems. A study of one hospital found that, rather than raising questions about their hospital’s linen-delivery service, nurses paid for taxis to deliver the laundry when there was no clean linen in the hospital closets. Inherently valuable qualities in a professional, including a commitment to a goal, vigilance, accountability, and independence, can work against the identification of areas where the organization could improve.

Addressing the workaround syndrome is not inherently difficult once it is recognized. One approach is to create a “parking lot” where people can document their workarounds. This could be a website or simply a bulletin board. When members of the team have downtime during or between proposals, they can address the underlying problems that resulted in the need for a workaround. The proposal business has peaks and valleys, and virtually everyone has downtime. Workarounds will not get addressed unless there are incentives for team members to use downtime in a productive way.

Cognitive Barriers

Even if an organization has promoted a culture of honesty where mistakes are dealt with openly and fairly, other deep-seated cognitive and psychological tendencies make it extremely difficult to gain a clear understanding of what transpired. One bias that is easy to observe and understand, and has long been studied by psychologists, is cognitive dissonance. When a person’s firmly held beliefs are contradicted by actual events, that person tends to not change his or her beliefs but rather to rationalize them and find ways to reinforce them. Reviewing what has happened to us is not “like replaying a tape. Rather . . . it’s ‘like watching create a “parking lot” where people can document their workarounds in a few unconnected frames of a film and then figuring out what the rest of the scene must have been like. . . . If mistakes were made, memory helps us remember that they were made by someone else’” (Newham 2008, Tavris 2007). Another example is the hindsight bias. Knowing the outcome of an event (we lost) colors

our perception of what happened. When an unknown manifests itself as something tangible, it becomes knowledge; before then, it was one of many unforeseen possibilities. In the proposal environment, it is easy to assume that the team should have known things that were perhaps unknowable and unpredictable. It is only in hindsight that a customer’s shift in perception appears obvious and inevitable. Dietrich Dorner uses the term ballistic behavior to describe a very human tendency to continue on a predefined course without stopping to examine consequences, just as a cannonball proceeds to its destination without there being any opportunity for us to control its course. Ballistic behavior preserves our sense of competency. However, because our knowledge is always imperfect, “we have to be able to adjust the course of our actions after we have launched them; analyzing the consequences of our behavior

is crucial for making these ex-post-facto adjustments” (Dorner 1997). This behavior regularly plays itself out in the proposal world, since time pressures add to the desire to stay on a predefined course of action even if it is not the right one. Other biases, well documented in the management-science and organizational-development literature, include denial, presumed associations, irretrievability, misconceptions of chance, overconfidence, positive illusions, egocentrism, and the confirmation trap. Each of these can contribute to a misperception and misrepresentation of what actually occurred (Bazerman 2002). Although these biases have traditionally been studied from a behavioral perspective, neuroscientists, through the use of magnetic resonance imaging, are now starting to understand the parts of the brain that contribute to decision-making. Physiological research is certain to offer more effective ways of understanding these cognitive processes. Biases and preconceptions can preclude an accurate depiction

of the actual proposal events. Everyone has attended a meeting or observed an event only to find later that their own recollection of the same occurrence differs markedly from that of other attendees. The high stakes in a proposal environment, when jobs, revenues, careers, promotions, and the financial future of the organization may hang in the balance, undoubtedly intensify the likelihood that one or more of these biases will color the analysis.

What can proposal teams do to compensate for cognitive errors? There is no simple remedy for overcoming thought patterns that are deeply established in our subconscious. Awareness is the first step. Recognition of the cognitive and psychological biases that color our judgment can minimize their influence.

Involving neutral (but experienced and knowledgeable) observers in the post-loss process can also partially offset many of the analytical biases that result in incorrect conclusions. Thus, whenever possible, it is advisable to have a qualified professional from outside the organization complete an independent audit of all the proposal documents and conduct interviews with participants. Although no account of what transpired will ever be completely free of bias, an outside observer is less likely to share the biases and preconceptions of the proposal team and the managers inside the organization. Of interest to organizations truly committed to learning is the formal “metacognition” process, which is aimed at educating decision-makers to improve their ability to recognize and correct their biases. Another approach is to ensure that key players on the team get regular feedback, a concept consistent with the notion of small losses. My own practice entails asking one or two people on the team to comment and critique my performance along the way. At first, I do not always get a lot of comment or criticism, but, if I keep asking, I do eventually receive feedback about my own blind spots, biases, and preconceptions.

Focusing on How, Rather than Why

It is very tempting to create new processes after a loss with the idea that the right process will fix all problems. The proposal business is, in fact, notorious for its worship of process, often at the expense of everything else. It is worth noting that the management-science literature shows that learning organizations tend to embrace principles rather than focus exclusively on detailed processes. Both principles and processes are important, but principles are particularly relevant to the competitive proposal environment because each deal is unique in its requirements, staffing, technology, customer preferences, and pricing, and it is unlikely that detailed processes can cover all the possible forms that a deal might take. In addition, the process without the principle is the “how” without the “why.” It is much easier to gain support and promote compliance when people understand the reasons behind what they are being asked to do. Principles enable a culture that promotes learning and improving. As Jeffrey Pfeffer and Robert

Sutton note in The Knowing-Doing Gap, “Operating on . . . a set of core values and an underlying philosophy permits . . . organizations to avoid the problem of becoming stuck in the past or mired in ineffective ways of doing things just because they have done it that way before” (Pfeffer 2000).

On my proposal teams, we often work together to create a list of principles. Honesty is a core value for me, and it operates at many different levels. It entails honesty in my communication with others, honesty in the assessment of the proposal by the review teams, and honesty in the proposal document itself, where we do not ever make statements we know to be false. Honesty is equally important in developing the price proposal. The estimates have to reflect an honest judgment about what it will take to accomplish the work. Once people understand this principle, the

processes (e.g., the requirement for a detailed basis of estimate) start to make sense. Such principles may not be universally liked, but they cease to appear arbitrary and meaningless.

Analysis Paralysis

Walt Disney was well known for saying, “The best way to get going is to stop talking and begin doing.” Principles come to life through actions. Errors and shortcomings discovered after a loss can only be fixed through action, and action means activity, not talking or writing or briefing. The tendency to fall prey to “analysis paralysis” is particularly prevalent in knowledge-intensive industries, where senior managers are often well-educated, intelligent, and inclined to over-think, over-model, over-brief, and over-talk without ever taking action. Learning by doing is proven more effective than any other teaching method for perfecting job-related skills. As Pfeffer notes, “Both the evidence and the logic seem clear: Knowing by doing develops a deeper and more profound level of knowledge and virtually by definition eliminates the knowing-doing gap” (Pfeffer 2000). Anyone who has taken proposal courses has experienced the difference between classroom learning and the reality of a live proposal environment, so learning by doing is imperative in our business. Nevertheless, it poses certain challenges. Apprenticeships, mentoring, and

shadowing can be expensive. Trial and error is not an acceptable approach when time and budgets are constrained, as they tend to be during a proposal. This means that organizations have to find ways to take action, to test-drive new approaches, and to effect organizational and personnel changes before the next big bid and before time constraints make it difficult to contemplate or implement change. The implications are clear: An organization that goes from one proposal to another without taking time to implement corrective actions is destined to continue repeating

the same mistakes.

Staying Stuck in the Past

Some teams have trouble letting go. Since organizations are reluctant to examine losses in detail in the first place, it seems as though moving on would be the easiest part of the cycle. Why not rush to get past something that is so unpleasant? Oddly, people often stay stuck, even in counterproductive and undesirable places. In his analysis of the creative process, Robert Fritz notes, “Shortly before prisoners are released, they often experience sleepless nights, anxiety, loss of appetite, and a host of other unpleasant feelings. This experience comes, paradoxically, after years of looking forward to the day when they will be released” (Fritz 1984). Some people and some groups have trouble bringing events to closure. Several guidelines are helpful here. First, as noted earlier, it is easier to move on if the analytical work and the resulting action plans are complete. In other words, finish the first three steps. Second, the work must be recognized as complete. It might even be necessary to mark completion formally with a banner, a statement, a short ceremony, or, at the very least, a message to all the participants. Time pressures and a lack of formality and ritual in the business world (and in life more generally) make it difficult to treat important milestones with the respect they deserve.

Summary of Obstacles and Remedies

This list of obstacles, as daunting as it sounds, is not exhaustive, and further research in other disciplines will certainly uncover more challenges. The techniques identified in this article are summarized in Table 1.

A Code of Conduct

Anyone can be magnanimous and gracious after a big win. It takes an extraordinary individual to demonstrate dignity and grace after a big loss. This is what separates the leaders from the managers. The leaders in other fields, such as Coach K, adhere to a code. We know the right code of conduct when we see it, but

one has never been articulated for proposal losses. Since losing is inevitable, it makes sense to establish a formal code. My own first draft of such a code consists of the following guidelines:

• Use an elevated level of courtesy and formality in all written and verbal communications, especially during the debrief.

• Notify everyone promptly of the loss, including all subcontractors and support personnel.

• Provide as much information as appropriate about the reason for the loss as stated by the customer.

• Initiate the four-step process immediately, and let the tea and senior management know what is going on at each step.

• Accept responsibility publicly for errors that have been accurately identified.

• Get back in the fight. Soon.

Conclusion

Losing proposals are a fact, a reality of competition. The science about the potential to learn from losing is equally clear: Failures are more effective teachers than successes. The inevitability of proposal losses provides regular opportunities to grow and learn, opportunities that are often squandered. No silver bullets exist to reduce the amount of time, attention, energy, and skill that it takes to complete a true lessons-learned process. Commitment to this endeavor has to come from the top, and there are mountains of resistance to be climbed. However, like many

difficult undertakings, the rewards are commensurate with the investment required.