The following is Part 1 of a two-part article by R. Dennis Green. Be sure to check out our first issue of 2020 for Part 2!

At the end of the year—APMP’s 30th, we take a pause to look back on our profession. What do we see?

Depending on how and where I look, I can see both dark and light, joys and challenges, yin and yang. I see a maturing profession, but one with a split personality.

The duality is this: On the one hand, our profession is built on precepts of need and persuasion that have been unchanged for generations, if not millennia. On the other hand, our profession is seeing tectonic degrees of change and innovation that are greatly altering and reshaping the day-to-day nature of our work.

That said, this is not really something to fret about. We’re lucky. In our profession, we get to have it both ways.

Part 1: Looking Back 40+ Years…

Part 1: Looking Back 40+ Years…

To a Profession Dramatically Changed

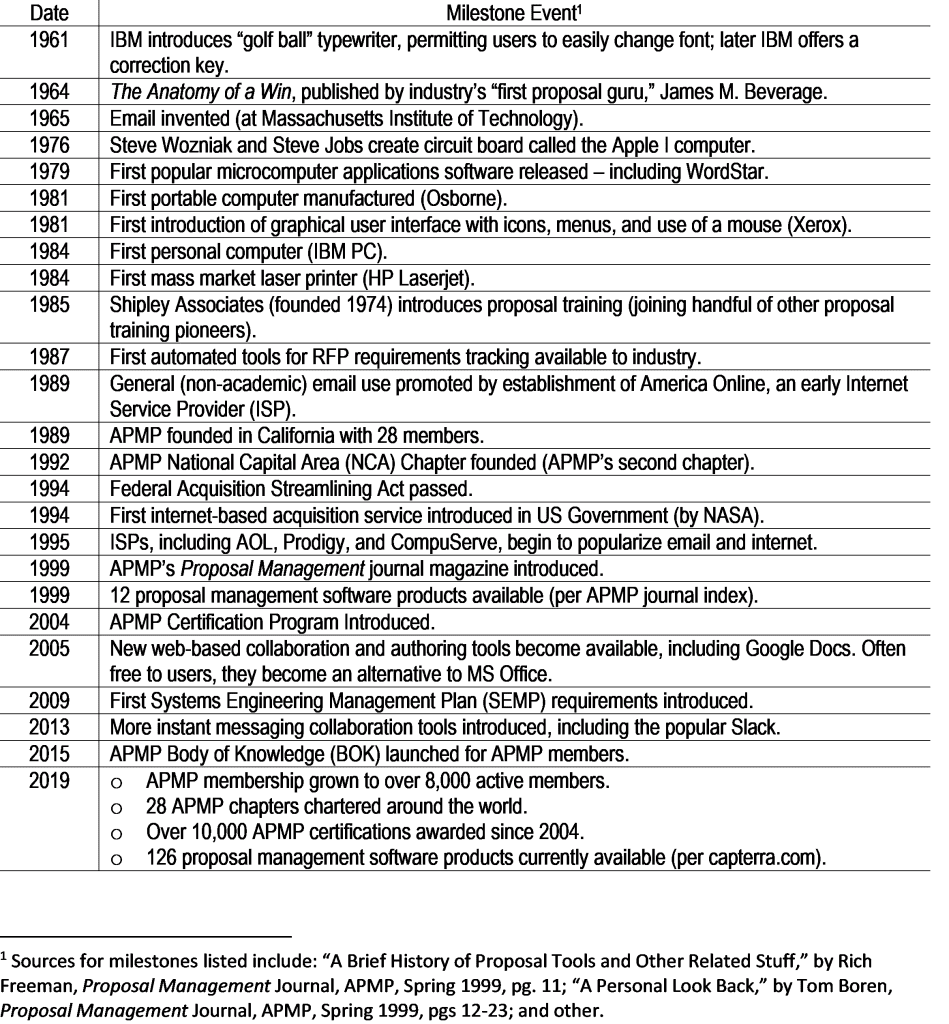

I love the proposal management profession. I must. I’ve been at it for 40+ years. And, I’ve witnessed change aplenty. Much of that change was driven by technology’s revolutionary advancements—from the introduction of personal computing to worldwide interconnectivity. The proposal management industry has also evolved in that same short timeframe. APMP wasn’t founded until late 1989, the same year as America Online (now AOL). That’s when many of my generation were introduced to the enticing mysteries of dial-up Internet modems and the once-familiar computer mantra “You’ve got mail.” Throughout this era, proposal professionals have had to be nimble. They’ve had to adapt. Here are just a handful of noteworthy milestones from this age of change:

This evolution has triggered many procurement industry trends. They include:

- Proposal page limits getting smaller.

- Proposal due dates becoming quicker.

- Hard copy deliverable requirements diminishing.

- More importance on being clear, resolute, and concise.

- More emphasis on graphics.

- More emphasis on oral and video presentations.

- Competitive intelligence easier to acquire and procure.

- Proposal management automation tools readily available at affordable prices.

- Proposal designs getting prettier and more polished.

- Proposal participants geographically disbursed.

- Youthful proposal teams thriving in a virtual world.

Of course, the products and services we propose are also affected by innovation. That future-focus is one of the things that makes our profession so enticing. It’s the perfect antidote to boredom. The subject matter of proposals keeps us focused on the future to come.

Personally, when I think of how the profession has changed, I flash back to the 1980s. Here are two snapshots to illustrate how proposal management has changed in my time.

Snapshot 1, A Massive Publications Burden. The publications burden on proposal teams was once enormous. On a 1982 bid I supported to the U.S. Navy for lead ship detail design and construction, for example, the full proposal inclusive of multiple volumes, program plans, and design specifications totaled thousands of pages for a single copy. Original author drafts were prepared on typewriters and in longhand over a period of 10 months. Authors collocated in central war-rooms. Drafts were hung on war-room walls to facilitate team collaboration. Airbrush artists “improved” the facilities photos prior to publication. Final proposal pages were mocked up on lightboards with T-squares. Subsequent changes were cut into page masters with X-Acto knives. Offset printing on etched metal plates was used to reproduce pages. Typesetting, pagination, and printing were started weeks in advance of deadline. A large truck was contracted to drive the pallets of proposal documents more than a thousand miles for delivery to the government. A “safe set” of documents was flown separately by business jet.

Today, we’re starting to realize the paperless dreams of a past generation. That massive publications burden I witnessed is a thing of the past.

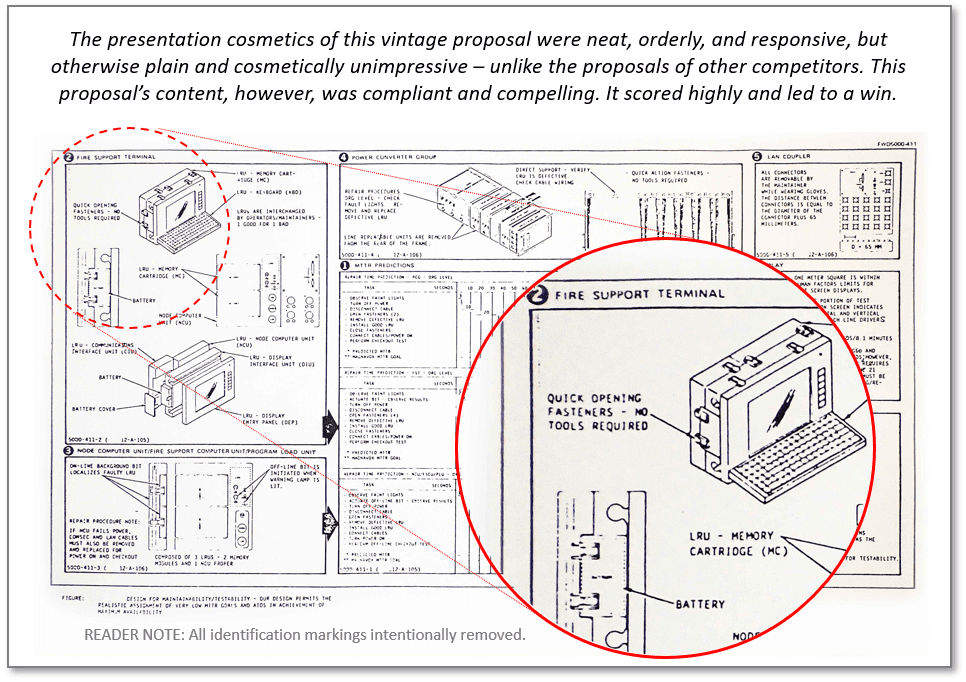

Snapshot 2, Good Content Versus Cosmetic Glitz. Like today, the 1980s was an exciting time of change and technological innovation. That innovation was typically reflected in the product or services being bid. It could also be reflected in how the team’s proposal was typeset, artfully rendered, and produced.

In 1983, I was part of a team supporting a large midwestern company on its field artillery system bid to the U.S. Army. This company was then pioneering impressive computer chip miniaturization technologies, and the field computer design they evolved for that Army application was robust. The company understood its customer. They custom-tailored a product solution.

To build their proposal, this company adopted a Graphics Oriented (GO) strategy with heavy reliance on fold-out graphics to document their technical, management, and support approaches. The proposal had over six hundred GO exhibits.

For reasons related to the high expense of then-new phototypesetting technologies, this company chose not to use them even though most other companies in its revenue class were. This company didn’t even use typewriters capable of printing proportional type. Instead, based on pencil input from authors, the foldout exhibits were composed using product drawings produced by company engineers accompanied by callouts and text printed in a plain non-serif font and in a single-size. The result was very ‘old school’ textbook in its look and approach. Cosmetically the graphics were somewhat plain and unadorned, as shown in one surviving work sample as Figure 1 (with identification markings intentionally removed). All the product drawings were in 2D or isometric format, consistent with engineering—if not proposal— practice at that time. To the team’s credit, all graphics were ably constructed, reader friendly, and inclusive of persuasive claims. Though cosmetically challenged, the proposal content was compelling. The bid scored highly. The company won.

Figure 1. Plain but Compelling 36-Year Old Work Sample

This offeror proposed innovative technologies that proved compliant and persuasive. It did not use newer technologies to typeset or package its proposal documents.

This experience suggests that a compelling solution (product or service) does not need to be hyped or artfully packaged to grade highly. Conversely, it suggests that elaborate and artfull packaging cannot overcome or mask an inferior or non-compliant approach.

Special thanks to Jayme Sokolow and Ashley Kayes for their pre-publication reviews.

Leave A Comment